Nichelino That’s how Steve Boykewich described the first chapter of Ingrid Rowland’s book about Athanasius Kircher and Baroque Rome:

http://aceliverpoolescorts.co.uk/news/after-reading-this-air-compressor-fault-summar-28877432.html

That strange, bitter Jesuit, Melchior Inchofer, who as censor of Kircher’s Coptic Forerunner had expressed such enthusiasm for the work, seems to have soured on his colleague’s enterprise some years later. Inchofer’s 1645 satire of the Jesuit Order, The Monarchy of the Solipsists, already presented a figure whose resemblance to the great performer of the Collegio Romano seems unmistakable, an “Egyptian wanderer,” who, seated on a wooden crocodile, “broadcast trifles about the Moon.”

Elsewhere in the same diatribe, Inchofer described the researches pursued by Solipsist, that is, Jesuit, natural philosophers. Although he died in 1648, before the publication of either the Pamphili Obelisk or the Oedipus, it is hard not to associate the beginning of the following passage from Inchofer’s satire with an image that Kircher used in both books: a scarab rolling its ball of dung through the planetary spheres:

“Philosophical works among [the Solipsists] are more or less of this sort: “Does the scarab roll dung into a ball paradigmatically?” “If a mouse urinates in the sea, is there a risk of shipwreck?” “Are mathematical points receptacles for spirits?” “Is a belch an exhalation of the soul?” “Does the barking of a dog make the moon spotted?” and many other arguments of this kind, which are stated and discussed with equal contentiousness. Their Theological works are: “Whether navigation can be established in imaginary space.” “Whether the intelligence known as Burach has the power to digest iron.” “Whether the souls of the Gods have color.” “Whether the excretions of Demons are protective to humans in the eighth degree.” “Whether drums covered with the hide of an ass delight the intellect.”

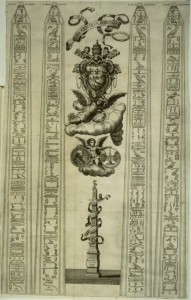

Kircher provided inspiration, the article declares, for Bernini’s Fountain of the Four Rivers, which is the pedestal for the obelisk above. I just saw Bernini’s clay and wood models for the Fountain at the fabulous exhibit at the Met – now just closed – which shows what we probably already know, that Bernini was the single greatest technical master of the art of sculpture that ever lived; the very Tolstoy of the chisel.

Before the press of Vitale Mascardi could produce Kircher’s monumental four-volume Egyptian Oedipus, the tireless father, now happily ensconced in a rhythm of phenomenal productivity, issued yet another preliminary study on Egyptian antiquity, this one dedicated to the pope himself on the occasion of the 1650 Jubilee. The Pamphili Obelisk (Obeliscus Pamphilius), a folio tour de force from the Grignani press, commemorated the erection of an Egyptian obelisk in front of the Pamphili pope’s family palazzo on Piazza Navona. The obelisk itself had begun its Roman career as an ornament in the sanctuary of Isis — brought from Egypt by Emperor Domitian (reigned 82-96 CE). In the early fourth century, just before losing to Constantine at the Battle of the Milvian Bridge (311 CE), another emperor, Maxentius, had transferred the granite needle to his own circus along the Appian Way, where it lay in pieces on the ground until Pope Innocent decided to move it yet again. Piazza Navona was an appropriate setting; the obelisk’s long, round-headed outline of this expansive urban space marked the site of the Circus of Domitian.

Here in 1648, the sculptor Gianlorenzo Bernini set the restored obelisk atop a delightful Fountain of the Four Rivers that gave full rein to his genius as designer and technician alike. Kircher, for his part, translated its hieroglyphic inscriptions and summarized them for engraving on the four granite plaques that still decorate the obelisk’s base. He probably did a great deal more, for it was his interpretation of the ancient Egyptian texts that guided Bernini’s design for the fountain, and the hollow mountain from which the fountain’s four rivers gush follows Kircher’s ideas about the structure of continents — he believed that all mountains stood domelike above huge underground reservoirs (he called them hydrophylacia) that fed the rivers of the world.

Post a Comment