Into the swamp.

I think most people whose love of nature is undimmed by mechanized life fantasize about the swamp: paddling a boat beneath a dense canopy of trees; being watched by motionless reptiles and cunning panthers; feeling the thud of living motion against the hull of your boat and wondering what it is; seeing strange blooms deep in the darkness and eyes at the edge of the campfire’s light. The swamp is primal and archetypal and hence godlike, containing its opposite; it is the generator and nourisher of life, but because it is so difficult for land animals to cross and so labyrinthinely featureless in its arrangement, it speaks to us of the danger that life always poses to life.

We were now in such a place, ducking in the high water to get beneath the buttonbushes and swamp-privets that clogged the boatways, entering dark passageways beside smooth-boled cypress and tupelos. Cottonmouths darted across our paths, intent on their course; alligators peered at us from inaccessible corners of the swamp.

But my restless mind does not stay mystical for long in an obviously distressed forest, as this was. Within minutes with the help of my guide I had learned the three tree species that were there – and in the standing water there were only three: bald cypress (Taxodium distichum – by far the dominant species), swamp tupelo, and water locust. But none of these species were regenerating. The absence of young cypress was particularly striking.

But my restless mind does not stay mystical for long in an obviously distressed forest, as this was. Within minutes with the help of my guide I had learned the three tree species that were there – and in the standing water there were only three: bald cypress (Taxodium distichum – by far the dominant species), swamp tupelo, and water locust. But none of these species were regenerating. The absence of young cypress was particularly striking.

“Why aren’t they regenerating?”

“The water’s too high,” was the response. “When the Mississippi flooded naturally, any one spot might flood only once every few years. Now the Atchafalaya gets water from the Mississippi every year. The young cypresses have to have a few years of low water to get established. That way they can get above the water level. They can’t get completely covered by the floodwaters for months at a time. It kills them.”

This was part of the contradiction of the area. The Atchafalaya was one of the last great cypress swamps left. But it was a fossil ecosystem: cypresses grow slowly and can live for thousands of years, and the ones growing here were relatively old (though not terribly large). But the swamp was becoming a river – a river a third as big as the Mississippi, in fact. This would not be a problem if swamps were forming elsewhere. But they weren’t. In fact, existing swamps elsewhere on the coast were increasingly falling victim to the influx of seawater, and none of the swamp species could stand salt water. The water and sediments the swamps needed were almost all in two places: in the Mississippi, where they were channeled behind levees and shot into deep water into the Gulf, where they never became part of any freshwater ecosystem, and in the Atchafalaya.

The fact that the swamp could only take a few floods per decade was indicative of the basic problem with nature: its terribly complexity, a complexity far greater than human thought, which is simple. As soon as we interrupt a natural system, we take upon ourselves the task of mimicking this complexity. We don’t typically have the patience for this kind of activity. The Atchafalaya could only reasonably serve as a floodway for the Mississippi if three or four other Atchafalayas were created, which could receive water in other years. Of course, cutting twenty-mile swaths of floodland through privately owned property would not be easy. But the Atchafalaya, big as it was, would not be able to function alone.

There was also about the place a kind of lifelessness, which I was surprised by. It was quiet – few birds, few insects, and we saw few animals. Accepting the fact that this was an unusual time – the water was very high and we did not visit a hummock where the animals might gather in the high-water – there is also simply the fact that this is a highly disturbed ecosystem. “The most important plants here are the old cypress,” Ryan (our guide) said. “That’s because they develop holes and cavities. The wood is extremely rot-resistant, so even with holes in them the trees can last for a long time. Since the birds and mammals can’t live on the ground or in the water, they need big, old trees.”

“And they’re all gone,” I said.

This one is just a shell.

“They’re not all gone, but they’re mostly gone. I’ll show you one, there’s one in this way.” He turned the boat and we came up within a minute or two to a six-foot-diameter tree. “See this one here? The whole swamp was full of trees like this – and a lot bigger ones, too. There’s only one reason why this tree was left.” We circled around it and could see – it was hollow. “There was no wood inside it. It’s just a shell. Now, it’s important – trees like this are perfect habitat – but look around. There are just a few of these trees around here. I can basically take you to each one, it’s like you get to know them individually. But the swamp used to be filled with these.”

“How old is this tree?”

“You can’t take a coring of a hollow tree, but based on the way these grow, it’s probably over a thousand years old.”

“They grow slowly.”

“They grow really slowly.”

“Even though we’re in the subtropics.”

Cottonmouth.

“You can tell they grow slowly from the logging industry. That’s one of the things we’re fighting against. Basically, these trees grow so slowly, and are so important, that we think they should be protected. But most of this land is private land. You can log in most of the basin and people do. But the trees grow so slowly that now most of it is either mining the cypress – that’s when they find old trees under the water, and they don’t rot, so you can pull them out and still use them – or they cut the trees down when they’re small and use them for mulch. It would take too long even to wait for them to become lumberable trees.”

“I read that your father had put pressure on Lowe’s and Home Depot and got them to stop selling cypress mulch from Louisiana.”

“Yeah, that was one of the things we did here at Basinkeeper. But we just found out there’s an operation going on in Baton Rouge where they’re chipping up the young cypress and shipping them to Europe. Europe has some new regulations coming into effect about generating a certain percentage of their electricity from sustainable sources, so they’re switching from coal to burning wood chips at some of their plants. And they can get cheap woodchips from the Atchafalaya. Cypress woodchips.”

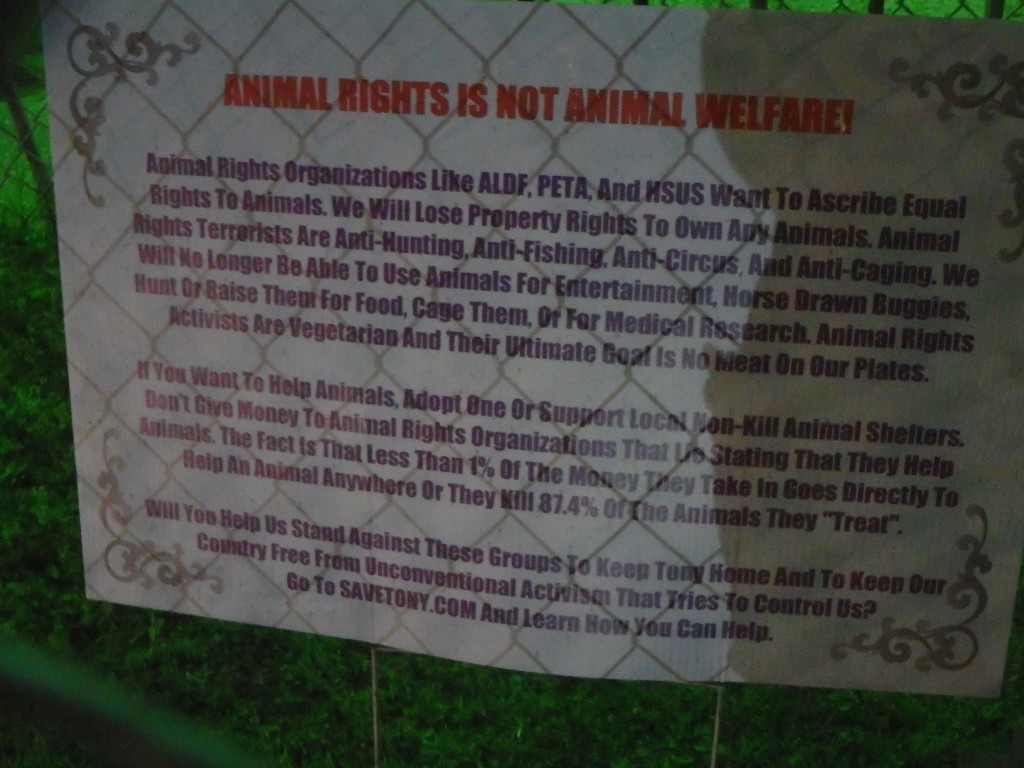

Basinkeeper was apparently trying to put pressure on the Louisiana government, but that was an uphill battle to say the least, despite the fact that the coastal wetlands are demonstrably the only truly effective hurricane protection for Louisiana’s biggest city. Louisiana was asking for federal money to rebuild its wetlands but did not want to tell private landholders what they could do with their land – the thinking being that if they wanted to make woodchips out of the wetlands they could go ahead and do it. It’s a free country.

The more time I spent with the cypresses, the more I was amazed. Their needles resemble the needles of sequoias, and they are, in fact, related. Living in hurricane country, the cypresses could never get as tall as the sequoias, but I suspect that the cypress forests that greeted Bienville and the other first Frenchmen here were as grand as the forests of the Sierras. The sequoias were preserved while the cypresses perished simply because it was so much more practical to kill the cypresses: while the sequoias fell and shattered and then had to be lugged down dry mountainsides, the cypresses plopped softly into the water and could be floated on out almost without effort to the Big Easy, which, it is no exaggeration to say, is a city of cypress.

Inveni urbem taxodinam, taxodinam reliqui.

Cypress is the reason why New Orleans is so beautiful today: all the filigree on all the houses is cypress, and even if left unpainted and neglected for decades the stuff does not rot. It is mealy-grained and odd-colored and was never used by the wealthy for finer purposes, and so the endless abundance of the swamps was used not for furniture but for building, and building anything and everything: bridges and mansions and fences and slave-quarters and shotgun-shacks and cheap mass-produced filigree, all of which gives New Orleans the appearance of being the most meticulous city in America for preservation, when in reality it is just lucky to have been surrounded by a whole hell of a lot of cypress.

Six hundred years will not be enough to grow those forests back, and it is still not clear where they would even have a chance to grow right now. Regeneration on the Atchafalaya, the country’s largest stand of bald cypress, is currently stalled.

“You can see here, when all the trees are gone, a lot of times what comes in is willow,” our guide said, “and that creates a totally different type of ecosystem.” The willow – I could not identify it to species, but it may be an exotic invader – grows like an overgrown bush, only twenty to thirty feet tall, fast-growing, fast-dying, and not creating the kind of deep shade and old-growth forest habitat the cypress and tupelo do.

The tupelos impressed me too. They do not, at first glance, look like the tupelos of the Catskills: they get extremely fat butts when growing in water, and as flowering, berrying trees they are a crucial food source for pollinators and birds in the swamp.

Spanish moss in bloom.

We saw few other plants in the swamp, which disappointed me, but the ground was so flooded there were little forbs to be seen. There was much buttonbush and swamp-privet, and on slightly higher ground much of the palustrine senecio native to the area. But there were not too many flowers.

“You want some flowers?” Ryan asked. “Take a look at this.” He reached over a plucked some Spanish moss from a tree. “It’s flowering now.”

And there, amidst the gray links of the moss – which is not a moss but a flowering plant – was a little orange flower. I was amazed – I had seen these everywhere and never stopped to notice their flowers. I loved them as I love all the small, unnoticed beauties of life.

But coming back from the tour I was pensive and even melancholy. There are times when I wish I had some other brain, that considered and imagined and appreciated less; or that would only appreciate what was there, and not look in the forest for the young trees to check its health, or ask why so many trees were the same age and suspect that the whole place had been logged at some point. I could feel how beautiful the swamp had once been; I could imagine what an uninterrupted forest of old-growth cypress would be like – a place to make the worshipper in all of us stand dumb with awe. And we had destroyed it.

Melancholia.

Heading back from the Atchafalaya we had to stop to get gas. The gas station at the exit had a big sign which said “TIGER,” which I presumed was just a local filling station’s way of copying Exxon, which used (uses?) a tiger as its mascot. But this was Louisiana, of course, so it had to be more insane than that. “Oh my God,” Randy said. “I’ve heard of this place. I never knew it was here.”

Heading back from the Atchafalaya we had to stop to get gas. The gas station at the exit had a big sign which said “TIGER,” which I presumed was just a local filling station’s way of copying Exxon, which used (uses?) a tiger as its mascot. But this was Louisiana, of course, so it had to be more insane than that. “Oh my God,” Randy said. “I’ve heard of this place. I never knew it was here.”